[ad_1]

Virtually on daily basis because the starting of 2020’s COVID-19 lockdown, I’ve texted with my mates Suzanne and Kate. We’re not all that related. I’m Black, and they’re white. We reside in several elements of the nation. They’re in long-term, child-free relationships. I’m married and have a toddler. However we’re all writers who share a deep reference to the pure world. And our writing displays our frustration on the means many individuals’s tales are erased from books held up as masterpieces of environmental literature.

Some years in the past I edited Black Nature: 4 Centuries of African American Nature Poetry. One of many anthology’s most outstanding statements was that Black individuals write with an empathetic eye towards the pure world. Due to erasures from so many narratives concerning the nice outdoor, the concept Black individuals can write out of a private relationship to nature and have accomplished so since earlier than this nation’s founding comes as a shock to many individuals. Conducting a overview of greater than 2,000 poems included in key nature-poetry anthologies and journals printed from 1930 to 2006—80 years of the environmental literary canon—I discovered solely six poems by Black poets.

However that doesn’t imply Black individuals weren’t writing these poems. Like so many writers who wander out into nature to search out themselves, Black writers additionally discover peace in connections to nature. Simply as sturdy because the pull of legacies of trauma that this nation inflicted—and inflicts—on Black individuals is the self-recognition a few of us discover in tales of hope and renewal that develop out of the wild world.

“Thanks,” one Black poet instructed me once I requested poems for Black Nature. “I’ve been writing this fashion my total life, however nobody has ever seen me on this mild.”

Individuals are a part of the pure world. And but, a great deal of canonical nature writing excludes individuals. Such writing spends a lot time in solitary meditative commentary that the writers ignore almost each human expertise outdoors their very own. Through the early days of the shut-in, in March, I texted Kate and Suzanne about some books I’d lately reread, together with Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, concerning the passage of a 12 months in Roanoke Valley. “Why,” I requested my mates, “had Dillard felt the necessity to erase the messiness of each mundane home undertakings and sophisticated nationwide politics from her e-book concerning the world?” Dillard expressed doubt that individuals would wish to learn a memoir by “a Virginia housewife,” so she left that a part of her personal story out. Her e-book additionally deletes the day by day experiences of many different individuals in her direct neighborhood. Across the time she was writing, a few of the most important integration struggles of the civil-rights period roiled simply past her door, however Dillard’s e-book maintains a segregation of focus and care. Such books don’t solely erase Black neighbors. They erase almost everybody.

“Dillard adopts the entire ‘man-alone-in-the-wilderness (or in her case the pastoral)’ trope,” Suzanne added to our textual content thread. “I imply, Edward Abbey was usually with one in all his 4 wives on the market within the desert, however they by no means present up. It’s pure fantasy.”

“That’s a part of why I like Amy Irvine’s Trespass a lot,” wrote Kate, referring to the wilderness activist’s 2009 memoir. “She’s so fucking sincere.”

Printed in 2018, Irvine’s subsequent e-book after Trespass is the contrarian meditation Desert Cabal. That e-book offers with the implications of the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Abbey’s Desert Solitaire—the identical Abbey who stayed within the desert as continuously by himself as with one in all his wives and their kids, although you wouldn’t find out about his household from what he wrote in that seminal e-book. On this case, there might be no extra applicable descriptor than seminal, a phrase usually used to laud the unmatchable genius of an particular person man.

Why disappear the individuals who individuals your world?

“Irvine doesn’t get that stage of affection for Trespass,” I wrote to my mates. “Partially as a result of she was so busy elevating her child that she couldn’t do the promotional work. However partly as a result of nature dudes like a sure sort of story.”

The good factor about texting is that I can keep on a dialog whereas vacuuming or stirring risotto. Generally seconds cross between messages. Generally lengthy days. The movement of ideas can meander as nicely. “It’s noteworthy that Dillard needed to jot down in a ‘genderless’ means (learn: presumably male),” I continued, “however they wouldn’t let her publish the e-book as A. Dillard.”

Suzanne, who had been offline, got here again to inform us a few of the phrases an editor used to switch the easy dialogue tag I mentioned in her manuscript. Most of the substitutions magnified a sort of servile femininity: I pleaded, I confessed, I admitted, I bustled, I apologized. “As in,” Suzanne wrote, “‘I’m sorry,’ I apologized.”

“Each time the phrase bustle comes up,” wrote Kate, “we’re doing a shot of tequila.”

“I have to learn Trespass,” wrote Suzanne.

In Desert Cabal, Irvine writes concerning the precautions she takes as a girl, together with giving cautious thought to what she drinks and with whom. She writes concerning the methods her life—the lifetime of a white, culturally and economically privileged girl—is commonly in jeopardy within the wild. Particularly when she’s within the firm of males.

I returned to an earlier second in our dialog—“There’s so little quotidian honesty in nature writing throughout that technology”—and began my very own contrarian environmental-lit record. A number of books by modern writers do pay considerably extra consideration to the realities of home life than I’ve seen in earlier generations. For The Guide of Delights, Ross Homosexual wrote small day by day essays about issues that delighted him within the on a regular basis world. Sooner or later, he even describes somebody doing the dishes. And I do know of at the least two locations in Deep Creek the place Pam Houston shares her procuring lists, together with what she deliberate to arrange for her housemates at dinner. Homosexual and Houston write of lives surrounded by each nature and other people. Although they’re generally vulnerable to ecstatic reveries, additionally they ship instruction on methods to reside within the sometimes brutal panorama of our world. In Homosexual’s case: in a Black man’s physique. In Houston’s: as a white girl and survivor of childhood abuse.

“Possibly what I’m lacking significantly is the parenting side,” I instructed Kate and Suzanne. “Youngster-free writers versus moms.” The routine duties that devour a dad or mum. I wasn’t studying about what retains me from writing one small essay a day.

I’m not judging the explanations an individual won’t be a dad or mum, or why they may not write about motherhood even when they do have a toddler. I’m being sincere in my very own writing about that for which I starvation.

Regardless that they aren’t moms themselves, Suzanne and Kate admitted an curiosity in such tales. “I feel Ellen Meloy and Eva Saulitis each write with quotidian honesty,” wrote Suzanne. “However as you say, each have been childless. You’ve got me operating to my bookshelves!”

Now we have to intentionally get hold of these books, as a result of the environmental creativeness we have been educated in didn’t admit kids, or the ladies who elevate them, into the canon of labor concerning the wild. Simply as one thing in that very same creativeness had not admitted Black writers.

But it surely’s not exhausting to search out writers who defy such limiting narratives. In a couple of of her nonfiction books, Barbara Kingsolver writes concerning the household backyard and her kids. Jamaica Kincaid’s My Backyard (Guide), which she printed in 1999, begins with a present of gardening instruments she acquired on Mom’s Day. In 2013’s Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer reimagines the methods we’d work together with the greater-than-human world. She additionally writes about classes she learns as a mom. And in World of Wonders: In Reward of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Different Astonishments, printed in 2020, Aimee Nezhukumatathil writes concerning the household she creates along with her husband nearly as a lot as she writes about her personal childhood and household of origin. Nonetheless, what’s the previous saying? The exceptions show the rule.

I didn’t write the rest to Kate and Suzanne about books that adopted or resisted the restrictions of this style, as a result of I bought caught up getting ready and serving my household’s dinner. Then the nighttime rituals: combing and braiding my daughter’s hair; asking, “Did you sweep your tooth and wash your face?”; eradicating still-unfolded laundry from the mattress so she may sleep. The thicket of human happenings—a unique sort of woods. Suzanne wrote, “Nothing extra pure in people than the messiness of giving delivery. She bustled.”

“Drink up, sister!” wrote Kate.

I could or might not have had a drink that night time. I didn’t write it down. What I do know is that within the rush earlier than choosing my daughter up the following day, I threw a handful of fruit right into a smoothie, with out turning off the blender’s blades.

Subsequent within the textual content chain: a photograph of my cupboards coated in vegetal goo. As an alternative of following up on concepts I shared with my mates or slicing again the winter scrabble that wilded our March backyard, I targeted on cleansing the kitchen partitions and cupboards and flooring.

I couldn’t draft a textual content in the identical means as so many elderly, white, principally male nature writers. Not on a morning like that. I couldn’t look away from the messiness. I wouldn’t wish to erase the goo, or my lady, or my Black arms scrubbing our kitchen from my account of the wild world I so deeply love.

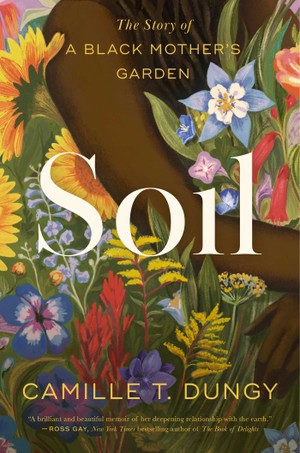

This essay has been tailored from Camille T. Dungy’s forthcoming e-book, Soil: The Story of a Black Mom’s Backyard.

Once you purchase a e-book utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.

[ad_2]